(Continued from part 1)

It’s fair to say that we’ve struggled at times, since launching Maluk Timor in the wake of our inglorious departure from Bairo Pite Clinic, to restore our credibility and elevate our rebranded organisation into the collective consciousness of our Timorese health partners. There are many other better-funded health NGOs in town and we’ve often felt like the new kid battling to make his mark on the world.

It wasn’t self-doubt: we always had confidence in the quality and sincerity of what we were doing and forged on ahead trusting that some day someone might notice us and see the value in what we do. The long and winding campaign to secure our MoU with the Ministry of Health was the defining story of 2018 and 2019 for us, so we began 2020 with fresh optimism that finally we could move forward. Maybe we’d be allowed to eat at the grown-ups’ table.

Then there was COVID-19 and the hurried exodus of internationals, with the result being that Maluk Timor became almost an overnight sensation, the new darling of the health sector. It was a recapitulation of the Steven Bradbury story to some extent: as all the other speed-skaters slipped and fell it was the last man standing who carried off the gold medal. But we mustn’t forget that he still had to be good enough to be in that race, and so did we.

Then there was COVID-19 and the hurried exodus of internationals, with the result being that Maluk Timor became almost an overnight sensation, the new darling of the health sector. It was a recapitulation of the Steven Bradbury story to some extent: as all the other speed-skaters slipped and fell it was the last man standing who carried off the gold medal. But we mustn’t forget that he still had to be good enough to be in that race, and so did we.

As I recounted in part 1, we had retained a strong, highly skilled and committed team in the country when others had been forced to retreat. Somewhat fortuitously, we had been preparing and drilling that team in precisely the skills that were needed for this crisis, so we were ready to respond when the call came.

Suddenly we were headlining the Australian Government’s aid response in Timor-Leste, and we were ‘besties’ with the senior directors of the government’s health response. I think my recognition of our new standing really struck home during one of many lengthy meetings with the Ministry of Health. I have attended my share of these and, as sometimes happens, on this occasion I had been summoned forward to sit at the main Boardroom table amidst the various national directors. During this five-hour-meeting news filtered through that the State of Emergency had been declared and that we would no longer be able to drive in Dili without a freshly laminated ID card from the Ministry of Health. We were shut down.

Impossible! We had a full training schedule underway!

The Whats App feed was going crazy as everyone scrambled to send their staff to the appropriate government department in a nearby building to compete for these ID cards which were evidently in very short supply. We tried to sustain our attention on the heavy discussions at the table but all of this was proving very distracting.

To my astonishment a senior government official – a man who had arm-wrestled me for two years as part of our MoU process – messaged me from across the room to ask how many ID cards I wanted. Trying not to be greedy, I responded with a request for twenty. Minutes later he very conspicuously manoeuvred himself through the formally-assembled meeting and deposited a pile of lanyards on the Board table right in front of me. Some of my friends from other health organisations looked on in horrified envy, while all I could manage was a sheepish smile, like the pimply nerd who had just been kissed by the belle of the ball. We had never been on the end of such privileged treatment.

To my astonishment a senior government official – a man who had arm-wrestled me for two years as part of our MoU process – messaged me from across the room to ask how many ID cards I wanted. Trying not to be greedy, I responded with a request for twenty. Minutes later he very conspicuously manoeuvred himself through the formally-assembled meeting and deposited a pile of lanyards on the Board table right in front of me. Some of my friends from other health organisations looked on in horrified envy, while all I could manage was a sheepish smile, like the pimply nerd who had just been kissed by the belle of the ball. We had never been on the end of such privileged treatment.

Maluk Timor was now being referenced daily by political figures in the press, on social media, and at every meeting we attended. Having thrown our team into the field at a time when so many others had been forced to recall theirs our collective expertise and enthusiasm for this work began to speak very loudly for us. This was aided by a newly-formed but very active Communications team who were lighting up Facebook in Timor-Leste on our behalf.

The tempo behind the scenes was absolutely furious. We were thrashing out new training programs, brokering new deals and partnerships, advising on all manner of emergency preparations, and trying to sequester and protect a group of recently-returned cardiac surgery patients from Australia. We doubled down on training, clinical and non-clinical, including taking the lead on a Psychological First Aid package that was in heavy demand.

Perhaps our best (or most ambitious) idea was to equip 43 Timorese doctors – the registrars from the Family Medicine Program whom we’d been training these past years – as educators who could take the COVID-19 training materials we had freshly developed to every health centre in the country. That’s the thing about Timor-Leste – almost everything we do as expats revolves around Dili, yet three quarters of the population live in small villages scattered throughout the rugged and forested mountains, with very difficult road access. Reaching the seventy or so government health centres outside of Dili is an enormous challenge, especially during a State of Emergency when travel is restricted.

We didn’t realise when we first dreamt up this scheme how critical this work was going to become. Our team worked day and night to create and translate a curriculum of COVID-19 training materials that were tailored to suit remote Timorese health centres. Our logistics team trawled the shops of Dili, many of which were closed down, to find buckets and taps, tarpaulins, gazebos, plastic twine, rolls of tape, and all manner of other oddities that we thought might be useful in spawning pop-up triage booths all over the country.

Four days of training, a few days of prep (including a factory-line of printing and laminating of posters, flow diagrams and signs), and some maddening last minute phone-calls as one of our partners withdrew their offer of nine 4WD vehicles, and the government announced another surprise public holiday… we were ready to launch.

Pulling together half a dozen partner organisations and manufacturing 17 teams to fan out across all 13 municipalities to reach literally every hospital and community health centre in the country in the space of ten days… it was a coordination nightmare yet a monumental achievement for everyone involved.

Our intrepid Timorese doctors braved the horrific roads of the wet season, the police checkpoints, and the frustrations of trying to run trainings in hospitals and health centres with either no power, no projector, no wall upon which to project, or no people to train. They were extraordinary: armed with their basic supplies they threw up triage booths and handwash stations wherever they went, in blazing sunshine or pouring rain.

We almost couldn’t believe it worked. Of course it was only a beginning, and it only raised the expectations of what we might do next.

Tempering those expectations were the growing challenges at home. With the school closed and school holidays over we were facing the same sense of dread afflicting working parents across the world: home-schooling.

We love being with our kids, but we’re really very happy not being their school teachers. And this particular point in our lives didn’t seem to be crying out for a lack of purpose, nor for want of something significant to do. My stomach churned as I flicked through the correspondence from the school which mapped out the 26 new profiles, log ins and passwords we needed to get our four children connected to this new reality. I felt like I was going to scream. This was clearly not going to just take care of itself.

Bethany, in her usual pragmatic way, got stuck in and created a homeschool corner. Levi, our self-appointed computer nerd, delighted himself with these new opportunities to download, install, sign up and log in to each of the 26 platforms on behalf of his siblings. Actually we’d have been a bit lost without him. Gradually, inspite of painfully slow internet and a general inability to watch anything that the teachers sent through in video format, Bethany gained a kind of functional ascendancy over the situation, admittedly with a bit more cussing than the children were accustomed to hearing. They’re learning all kinds of new things at home.

Worryingly though, their imaginative play has changed. Now the toys sit around Boardroom tables and have crisis meetings.

On the weekends we would try, when we could, to get out and about. Taking a few of our Maluk Timor volunteers with us, we went for hike up a river valley to a freshwater weir. Micah counted his falls along the way and registered double figures. On the way home we were intercepted by an afternoon storm which soaked us and every possession we carried, and made the car smell like ‘wet dog’ for a week, but it made the excursion all the more memorable.

We narrowly missed out on the ultimate memory-making experience of being either cut off or swamped in the river-crossing on the way home. That would have made for a more compelling tale.

Notwithstanding the sense of impending tragedy that troubled us night and day, these weeks were perhaps the most rewarding that Maluk Timor had ever enjoyed.

However, the uneasiness was unrelenting. The case numbers of COVID-19 slowly climbed in Timor-Leste – ten, then twenty – as returned Timorese students from Indonesia brought the infection home with them. The government’s quarantine and surveillance processes largely held back the tide but the likelihood of leaks seem to increase each day. I braced myself for what was coming, but was utterly unprepared for what was about to unfold.

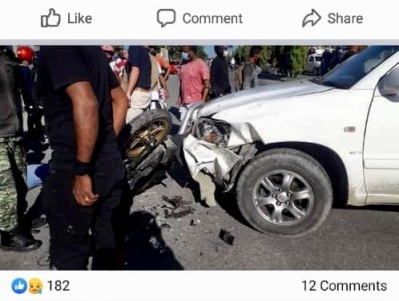

On a Tuesday morning, swinging my Kluger around in a U-turn exactly as I’d done hundreds of times before, I saw some oncoming motorbikes coming up the dual carriageway toward me. This was hardly unusual and, at the typical low speed of Dili traffic, one generally just nudges the car forward slowly and everyone else makes way. However, with fewer vehicles on the road than usual, one of the motorbikes was eating up the open road between us at great speed, closing in on me. I aborted my U-turn and halted, leaving an avenue a-lane-and-a-half wide in front of me, through which he could easily pass by adjusting his course just a few degrees. However, his head was turned to share a joke over his shoulder with his female passenger. He didn’t even see me until the impact was unavoidable.

His motorcycle thundered into the left side of my now stationary car, forward of the front wheel. The motorcycle went virtually no further, other than lifting its rear end to catapult its two riders over the handlebars and on to the road. The laws of physics dictated that the greatest leverage was applied to the rear passenger who, after being propelled high through the air, landing grievously on her unhelmeted head.

If you prefer to avoid grisly descriptions of road trauma I would suggest skipping down to the next photo.

I leapt out of the car and ran to the woman, finding her convulsing on the road, her face covered in blood-soaked hair. ‘She’s caved in her skull’, I thought, ‘and she’s going to die in front of me.’ I swept the hair from her face and positioned her to breathe, for what good it would do her. But then her seizure subsided, and she lay still, eyes open, breathing haltingly. It didn’t look good.

I attended the other passenger and found him conscious on his back, his helmet on the road nearby, and his right thigh swollen and shortened. That was a broken femur for sure, but he appeared otherwise intact.

The next thirty minutes were utter chaos. This particular road is the major artery of Dili and this tragic scene now occluded it entirely. It was around 8:30am and traffic was building up on all sides, and so was the crowd. The practice in Timor-Leste is to stop at an accident and, rather than rendering assistance, compete to capture the most horrific footage available to post on Facebook. In spite of my many attempts to stop people from recording the action, I knew I was being immortalised for the nightly news.

It felt like an age before either police or ambulance arrived, though some of my staff arrived at the scene to support me long before then. A Good Samaritan in the form of an unknown Timorese nurse was my strongest ally, phoning emergency services, providing basic care, and keeping the crowd at bay. These scenes can become combative here, but thankfully there was no hostility on this occasion. To my relief the young woman’s condition continued to steadily improve, and she began moaning and trying to get up. Soon afterward she was carried into the back of a ute and hurried to hospital. Then the ambulance, police and military all arrived in force, and order was quickly restored.

My car was impounded, I drafted my statement for police, and then I received the surprising news that the woman was apparently in good condition, with only a minor graze to the forehead. She was being discharged from hospital. I was stunned and relieved. My kids took it as an answer to their prayers which they had been faithfully sending heavenward since the minute they had heard about her. The young man would need time to recover from his broken femur but could also be considered to have cheated death on this occasion.

Rattled and distracted, I left work early and returned home. For four years I had safely endured the chaos of Dili roads… until now. I felt a range of emotions but mostly I feared for the wellbeing of the two riders. I would be made to pay – irrespective of fault there was only one party with any means to make reparations – but that could not have concerned me less. I just hoped everything would turn out all right.

Meanwhile, through the afternoon we began receiving hundreds of photos from our teams in the field. The photos detailed unheralded success in running trainings and setting up COVID-19 preparations simultaneously all over the country, some of them almost 12 hours drive away.

That evening I cobbled a few photos together into a Facebook post and shared it with every senior health figure I could think of. Maluk Timor was on the main stage now and I was inexpressibly proud of what was going on in our name.

Having posted my news and begun answering some early responders something else broke through into my social media feed. It started as a whisper, just a rumour… but within minutes Facebook and Whats App exploded with the revelation that Timor-Leste’s ultimate warrior-physician, Dr Daniel Murphy, had died unexpectedly in his home, in his mid-70’s.

If you know us, or you know this blog, then you know something about Dr Dan already. I won’t attempt to eulogise him here as there are others who will do that far better, but suffice it to say that Dr Dan was an American physician with a lifelong track record of serving the underdog who had given the last 21 years of his life to the people of Timor-Leste. He is a national hero, having done more for the health of the Timorese people than anyone else in their history. In the midst of the conflict in 1999 he threw together an impromptu clinic in Bairo Pite, a crowded and lowly suburb of Dili, and it grew to become one of the busiest hospitals in the country. It was where Bethany and I began our work in Dili in 2016.

Right up until his death Dr Dan toiled relentlessly for his patients and was revered as a saviour of the Timorese people, particularly the most vulnerable. His death was met with an overwhelming outpouring of grief from all quarters, just as the crowd at his cremation and funeral violated all of the country’s social distancing rules.

Many of you know that our own relationship with Dr Dan was complex. Having worked as his Medical Director in 2016 and 2017, I would say that he was a man much easier to admire from afar. However, in spite of a troubled working partnership there was never any lack of good reasons to respect him and his extraordinary work, and I can honestly say that he deserves his place within the highest echelon of Timorese heroes.

The death of this towering figure has brought a deep and pervasive sadness to the country and comes at a time when heroes are in short supply. What will become of our old stomping ground, Bairo Pite Clinic, without him? Where will the people of Timor-Leste turn when all other hope is lost? Their champion is gone, though he will surely never be forgotten.

The death of this towering figure has brought a deep and pervasive sadness to the country and comes at a time when heroes are in short supply. What will become of our old stomping ground, Bairo Pite Clinic, without him? Where will the people of Timor-Leste turn when all other hope is lost? Their champion is gone, though he will surely never be forgotten.

It rounded out a very strange day for me personally. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to find a way to unpack the swirling maelstrom of emotions that I experienced through that period of 24 hours.

That was only a week ago, yet it feels like it all happened in a distant age. The inconsistency of our perception of time has never been more apparent to me than in these past months during which some days have felt like they’ve contained a month’s worth of action, yet a week can slip through my fingers with such rapidity that I can scarcely tell you what it contained.

This week the focus has been about launching our new smartphone app, called ASTEROID. This app was supposed to be deployed in September or October as part of a project to strengthen Timorese health centres in detecting and mitigating infectious threats. This was long before we knew about COVID-19. Then suddenly, when we needed a way of providing clinical training to clinicians all over the country with no time to lose, the app was on hand.

Our partners, Catalpa International, had powered into action and launched the app a full six months early. Now I’ve got a whole team working on uploading content in English and in Tetun, and we’ve got hundreds of Timorese health workers from the remotest corners of the country signed up and connected. This tool is going to overcome the expected obstacles of tightened restrictions for travel and meeting in groups. It gives us a conduit through which we can reach clinicians everywhere with the most up-to-date information as the pandemic changes.

Our partners, Catalpa International, had powered into action and launched the app a full six months early. Now I’ve got a whole team working on uploading content in English and in Tetun, and we’ve got hundreds of Timorese health workers from the remotest corners of the country signed up and connected. This tool is going to overcome the expected obstacles of tightened restrictions for travel and meeting in groups. It gives us a conduit through which we can reach clinicians everywhere with the most up-to-date information as the pandemic changes.

But I’m a little weary, and my back is sore from the constant muscle tension that comes from perpetual urgency. I can only hope that all the nervous energy will amount to something and that Timor-Leste can withstand the coming storm.